Update: A few people have been asking me for the code for generating these graphs, so I organized some of the old code and uploaded it here: schwarzschild.py.

To find the trajectory of anything in General Relativity, usually you only need the metric tensor, from which you can obtain the geodesic equations. Nevertheless, a common problem that arises in cosmology is that as soon as we depart from the simplest homogeneous models, the task of finding solutions to the geodesic equations quickly becomes an intractable analytical problem.

In this post are some notes of how to perform numerical integration of light paths in the Schwarzschild metric.

Differential equations of orbit

The Schwarzschild metric is one of the most famous solutions to the Einstein field equations, and the line element in this metric (in natural units $c = G = 1$) is given by:

$$ds^2 = -f(r) dt^2 + \frac{dr^2}{f(r)} + r^2(d\theta^2 + \sin^2 \theta d\phi^2)$$

We are interested in the trajectory of a light ray in such a metric. Since the metric is spherically symmetric, any light ray that starts with a certain $\theta$ must stay in the same $\theta$ plane, hence we can arbitrarily set $\theta = \pi/2$ and do away with all the $\theta$ terms.

Light follows a null (lightlike) trajectory given by $ds^2 = 0$. In the absence of external forces, it should also travel along a geodesic. These are governed by the geodesic equations, which can be derived using Euler-Lagrange equations. Due to the symmetry of the metric, applying the Euler-Lagrange equations to the metric gives us two conserved quantities:

$$f \dot{t} = E = \text{constant}$$

$$r^2 \dot{\phi} = L = \text{constant}$$

where an overdot refers to derivative with respect to an affine parameter $\lambda$.

Using the null condition, we have

$$f\dot{t}^2 - \frac{\dot{r}^2}{f} - r^2\dot{\phi}^2 = 0$$

This can be expressed in terms of $\dot{r}$, and differentiating again gives the second-order differential equation for $r$:

$$\ddot{r} = \frac{L^2(r - 3M)}{r^4}$$

This can be easily converted into a first-order differential equation to be solved numerically by setting a variable $p = \dot{r}$. So we have these 3 differential equations to compute numerically:

$$\dot{r} = p$$

$$\dot{p} = \frac{L^2(r - 3M)}{r^4}$$

$$\dot{\phi} = \frac{L}{r^2}$$

(This can of course be solved analytically in the weak gravity limit, which gives the light bending equation $\Delta \phi = 4M/b$ where $b$ is the impact parameter.)

Initial conditions

In principle, we need the initial values of $r$, $p$, and $\phi$ to start the numerical simulation. However, if we fix the incoming velocity to be horizontal, then we would only need to specify the initial $x_0$ and $y_0$ coordinates.

We can take $\dot{t} = 1$ for convenience. The initial conditions can then be derived from the null condition and they are as follows:

$$r = \sqrt{x_0^2 + b^2}$$

$$\phi = \cos^{-1} \left ( \frac{x_0}{r} \right )$$

$$\dot{r} = p = \cos{\phi}$$

$$L = r^2 \dot{\phi} = r \sqrt{1 - \dot{r}^2}$$

Then, the only free parameters to specify $b$ and $x_0$, in addition to mass.

Graphs

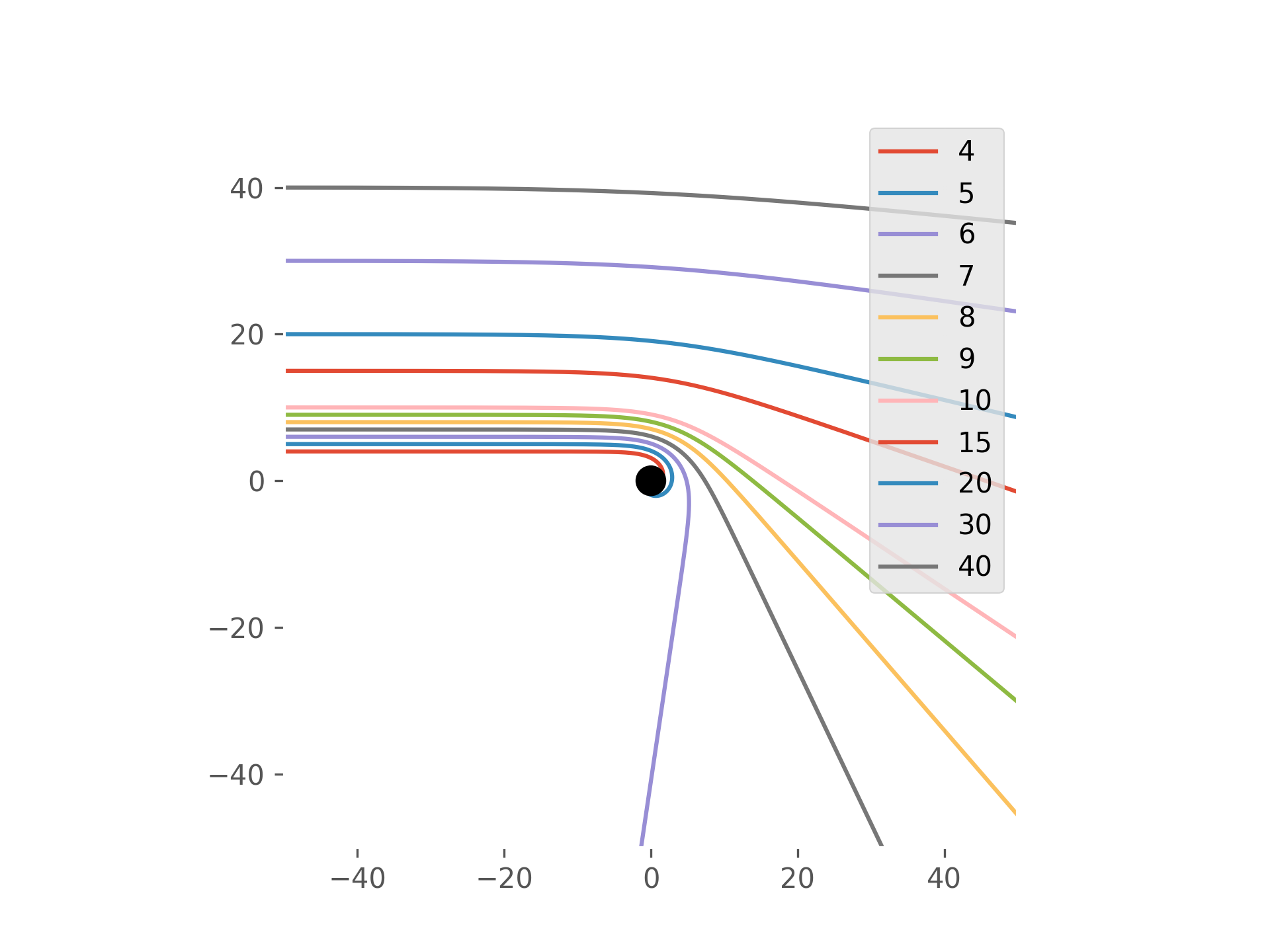

For a mass of $M = 1$ (corresponding to Schwarzschild black hole radius of 2), this is a plot of the trajectories with different impact parameters $b$:

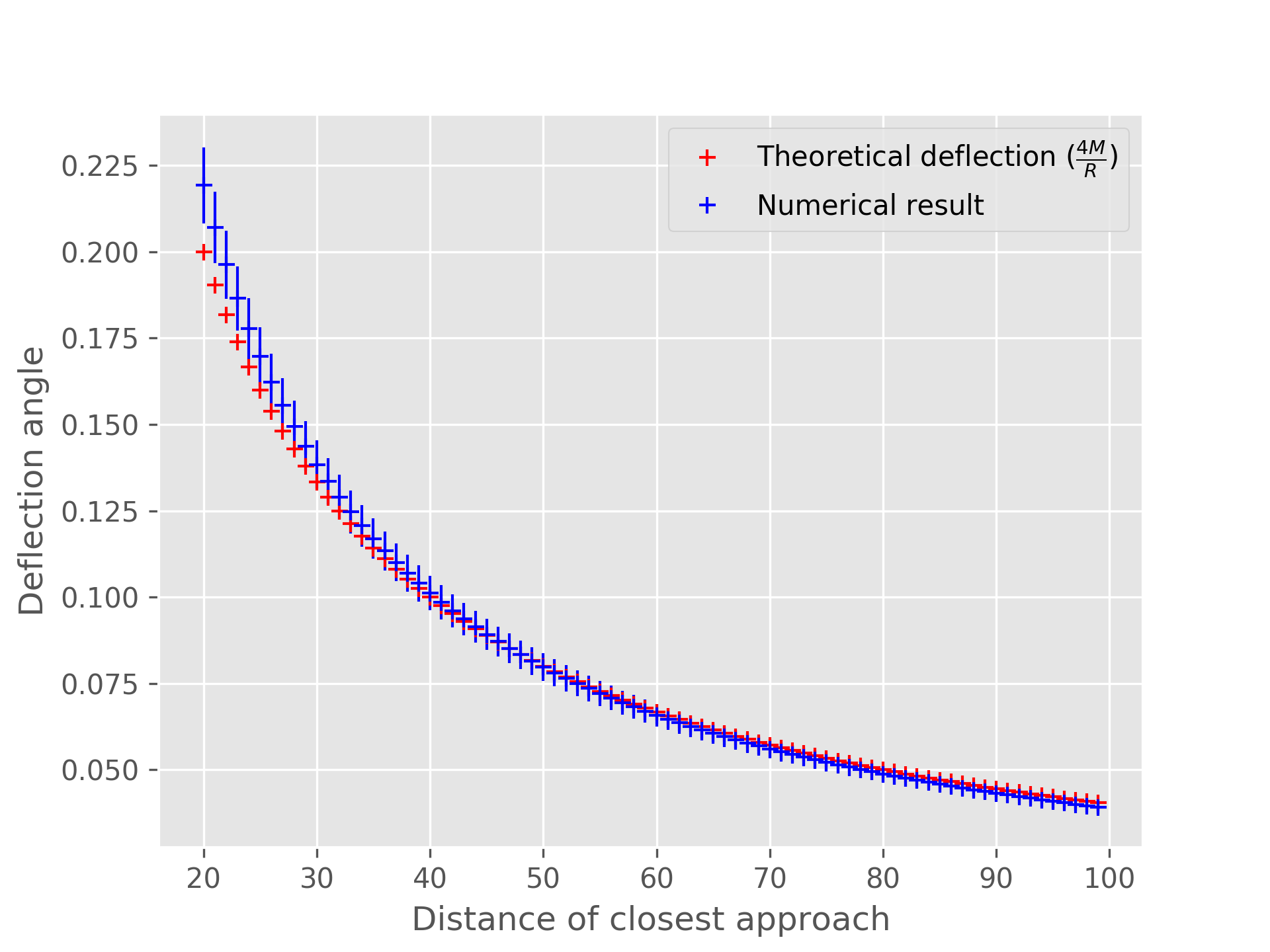

And they do fit quite well with the theoretical deflection angle $4M/b$ for large impact parameters: